Historical timber buildings by framing types

[edit] Light roundwood skeletal

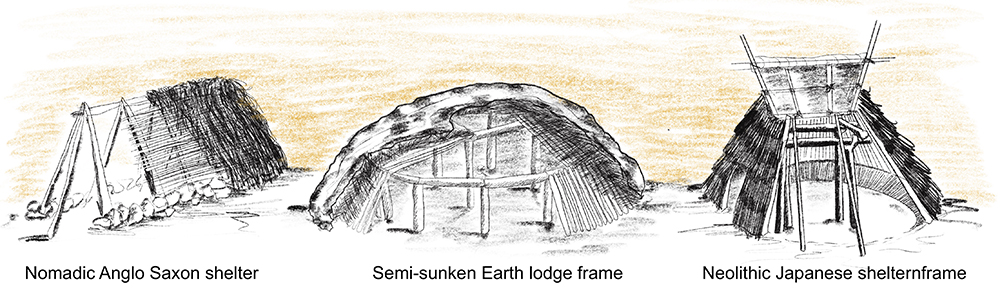

The oldest form of timber construction is what one might call a frame construction which is made using young growth round wood poles, here we call this round wood skeletal. Some of the earliest forms of basic shelter would have been made from natural found materials such as reeds, leaves, grass or bark laid over a simple frame of full branches that did not need cutting or slicing. Whilst early humans may have been nomadic, the frames could have been clad with animal skins and bound with natural reeds, often triangular and easy to erect and disassemble, commonly referred to as an early form of yurt.

The first recordings of a yurt were made by Herodotus of Halicarnassus who described yurt-like tents as the dwelling place of the Scythians, a horse riding-nomadic nation who lived in the northern Black Sea and Central Asian region from around 600 BC. Simple braced frames structures or reed hut shelters can still be found today in places like Sudan and Iraq, whilst yurts can be seen in Central Asia.

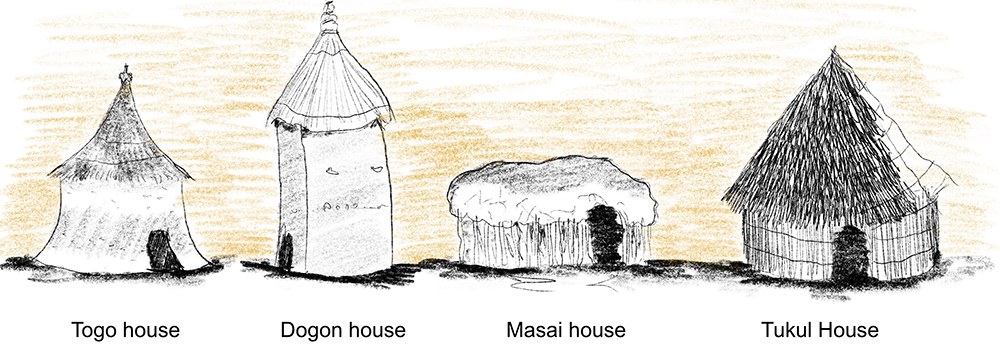

In places like the Cones of Cappadocia dwellings were constructed directly from soft volcanic stone without the use of timber. Other dwellings such as those found in Togo and Timbuktu were built with solid earth wall bases and thin wood and straw roofs. Hybrid structures using a timber skeleton as the primary base of the walls, plastered with wet earth and clay, might be seen in the Masai tribes in East Africa.

In Ethiopia, in the late 1800’s as timber stocks around Addis Ababa ran bare due to use as building material and fuel for a growing population, the king at the time planted Blue Eucalyptus due to its ability to grow quickly and ot regrow from stumps (early coppice wood). The Tukul or Sarbet grass house thus became a common round wood skeletal form of shelter, made with coppice round wood, wiht a triangular roof sitting on a circular structure of timber and reed that was then plastered in clay and earth. Many other examples of these simple timber round wood structures forming the basis of shelter, tents, and hybrid earth structures exist around the world. Examples can be found in the excellent pictorial essay book 'Shelter', first published in 1973 by shelter publications.

[edit] Roundwood base frame

Whilst this section relates very much to the previous, it differs in that this describes a time when people started to use larger sections of timber to create what might be described more as a frame rather than a skeleton structure. Initially also primarily using round wood but with larger sections, these frames were more rigid and stable on their own rather than in combination with the cladding of earth and other materials.

The earlier type of Anglo Saxon shelter (450-1066) would have been a very simple rectangular shape, single story with a pitched roof and no walls. As communities became more settled, roundwood framing evolved into more substantial base structures that could support thicker cladding or earthen walls. Rather than purely forming the roof or temporary shelter, roundwood began to provide continuous foundations for permanent dwellings. Circular timber rings, upright poles, and radial roof structures became common in regions with reliable long-term coppicing or abundant sapling species.

These roundwood bases often served as hybrid structures—timber providing the skeleton, while local materials such as clay, straw, and earth formed the mass. Traditional African and Middle Eastern dwellings, as well as many Indigenous forms of long-term housing, built strength out of simplicity. Roundwood, unprocessed and full of natural taper, offered remarkable durability when combined with earth plasters and wide eaves.

[edit] Log construction

Log construction emerged in heavily forested regions, particularly across Scandinavia, Russia, and parts of North America, where straight, slow-grown conifers could be cut and stacked horizontally. Instead of delicate poles, these early builders used whole trunks, notched at their corners, to create stiff, weather-resistant walls capable of withstanding harsh winters. The refinement of corner-notching techniques, such as the saddle notch and dovetail, allowed for airtight joints long before metal fasteners were common.

As log buildings spread, they became synonymous with frontier life and self-sufficient construction. Settlers could produce walls, floors, and roofs using only axes and saws, and the inherent thermal mass of the logs provided natural insulation. Log construction thus represents one of the first timber systems designed for extreme climates and long-term occupation.

[edit] Stilt construction

In regions prone to flooding, monsoon climates, or coastal tides, timber was elevated above the ground on stilts to protect against water, pests, and damp. This approach appeared independently across Southeast Asia, Oceania, West Africa, and parts of the Americas. The technique used long, straight poles planted directly into the soil or resting on stone pads, supporting lightweight floors and walls above.

Stilt construction not only improved durability but also transformed the way communities interacted with their environment, allowing settlements to expand across wetlands, riverbanks, and coastal edges. Timber’s strength-to-weight ratio made it ideal for these raised platforms, and the method remains central to vernacular architecture in flood-prone regions today.

[edit] Post and beam

Post-and-beam construction marked a shift from using timber in its natural form to shaping it into squared posts and beams capable of spanning greater distances. Large upright posts supported heavy horizontal members, creating open internal spaces for communal halls, barns, or temples. This system allowed builders to separate the load-bearing structure from the wall infill, enabling more flexible layouts and improved ventilation.

Civilisations across Asia and Europe refined post-and-beam carpentry into high craft, introducing joinery systems such as mortise-and-tenon, scarf joints, and wooden pegs. Its clarity, strength, and modularity set the foundation for many later timber systems, including medieval halls and the European oak frames of the Middle Ages.

[edit] Cruck frame

The cruck frame evolved in medieval Britain, where paired curved timbers, split from a single tree, formed arch-like blades that carried the roof’s weight down to the ground. Instead of relying on straight beams, builders utilised naturally curved trunks, embracing the irregularities of native hardwoods. These A-shaped frames created tall, open interiors suitable for longhouses, barns, and early farm buildings.

These frames came from an understanding of the material resources, because unlike many softwood species that grow quickly and in large amounts, UK hardwood forests were now planted in ordered rows but irregular and natural. This meant the timbers too were irregular. This is unlike for example some French planted forests which were specifically planted in tight rows to encourage straight growth of hardwoods, to produce the straight timbers needed for example in the the wine barrel making industry.

Crucks demonstrated an ingenious use of local tree forms, particularly in regions lacking long straight timbers. Their organic geometry remains one of the oldest and most distinctive forms of framed construction in northern Europe, celebrated for its elegance and structural efficiency.

[edit] Green wood framing

Green wood framing relied on freshly cut timber that retained moisture, allowing easier cutting, bending, and jointing. Medieval carpenters across Europe valued green oak and other hardwoods for their workability; once assembled, the timber shrank and tightened around its joints, increasing structural strength naturally over time.

This technique also aligned closely with coppice cycles and sustainable woodland management. Builders selected trees specifically for their grain, curvature, and moisture content, creating frames that were both responsive to the material and deeply connected to forestry practices.

[edit] European Oak framing

By the late medieval period, oak framing became a hallmark of European craftsmanship. Heavy timber structures with intricate joinery formed the backbone of cities, from townhouses and guildhalls to tithe barns and market structures. Oak’s density, durability, and resistance to insects made it the premium choice for long-lasting frames, often left exposed internally and externally.

These frames demonstrated high precision and cultural refinement: jettying, complex trusses, carved braces, and decorative infill panels became architectural signatures. Many such structures still stand today, a testament to the strength of handcrafted joinery and the exceptional longevity of well-seasoned oak.

[edit] Balloon frame

The 19th-century balloon frame revolutionised building in North America by replacing heavy posts with long, continuous, lightweight studs. Cut from inexpensive, machine-milled softwood, these vertical members ran from foundation to roof, joined by mass-produced nails rather than traditional joinery. This drastically reduced labour and cost, enabling rapid expansion of housing during industrialisation.

Balloon framing’s simplicity made it accessible to settlers and builders with minimal training, transforming timber into a material for fast, standardised construction. However, the continuous stud cavities also posed fire risks, influencing later transitions to safer systems.

[edit] Platform frame

Platform framing evolved from balloon construction to address fire safety and improve buildability. In this system, each storey is built as an independent “platform,” with floor decks interrupting vertical cavities and providing fire stops. Shorter studs, easier handling, and modular sequencing made platform framing the dominant method for timber housing in the 20th century.

Its practicality and adaptability allowed for wide adoption internationally. Combined with sheet materials like plywood and OSB, platform framing created efficient, standardised envelopes suitable for suburban growth and mass-produced housing.

[edit] Insulated log wood

Modern insulated log systems combine the visual and tactile qualities of traditional log construction with contemporary performance standards. Engineered laminated logs, internal insulation layers, and precision machining create tight-fitting walls with improved thermal efficiency and air-tightness.

These systems maintain the aesthetic warmth of natural timber while addressing energy regulations, condensation risks, and durability. They represent a hybrid evolution—roots in ancient log craft, but refined through modern building science.

[edit] Unitised timber frame

Unitised timber framing introduces pre-assembled wall or structural panels manufactured off-site for quick installation. Unlike traditional stick-built methods, frames are produced in controlled factory environments, improving accuracy, reducing waste, and speeding up construction.

This approach supports repeatable, high-quality building systems and integrates easily with insulation, windows, and services. Unitised systems play a key role in schools, housing, and commercial timber projects where predictability and programme certainty are essential.

[edit] Engineered wood frames

Engineered timber products—such as glulam, LVL, and CLT—expanded the possibilities of timber framing beyond what natural wood could achieve. By bonding layers of timber into strong, consistent elements, builders could span larger distances, carry heavier loads, and design more complex structures.

These materials enabled multi-storey timber buildings, long-span roofs, and sculptural forms previously unachievable with traditional methods. Engineered wood marks a pivotal moment in timber’s transition from vernacular craft to high-tech structural material.

[edit] Modular systems

Modular timber systems take prefabrication further by constructing entire volumetric units—rooms or sections of buildings—off-site, then transporting them for rapid assembly. This method offers extraordinary speed, quality control, and reduced on-site disruption, making it attractive for housing, hotels, and student accommodation.

Timber’s light weight and environmental performance align naturally with modular manufacturing. As carbon reduction targets rise globally, modular timber is gaining traction as a low-carbon alternative to concrete and steel modular systems.

[edit] Massive wood monolith

Massive wood monolith construction uses thick, solid timber panels or stacked elements to form entire walls without cavities. Historically seen in block-haus systems and modern variations like Brettstapel or dowel-laminated timber, these structures rely on the mass of wood itself for strength and thermal buffering.

Monolithic timber offers both simplicity and durability. With few mechanical fasteners and excellent acoustic qualities, it is increasingly explored in sustainable architecture, providing a natural, breathable envelope suitable for eco-focused projects.

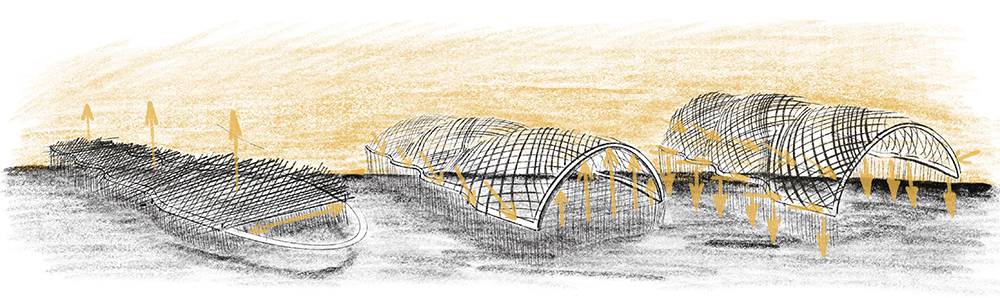

[edit] Gridshells

Timber gridshells merge traditional flexibility with modern engineering. Thin, often green, timber laths are bent into double-curved shapes and fixed into position to create lightweight yet strong shells. Though appearing contemporary, the technique recalls ancient bent-wood traditions and basket-making principles applied at architectural scale.

Gridshells achieve remarkable stiffness with minimal material and allow for expressive, organic forms. They embody timber’s dual identity as both a craft material and a medium for advanced structural innovation.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings

Featured articles and news

Future Homes Standard Essentials launched

Future Homes Hub launches new campaign to help the homebuilding sector prepare for the implementation of new building standards.

Building Safety recap February, 2026

Our regular run-down of key building safety related events of the month.

Planning reform: draft NPPF and industry responses.

Last chance to comment on proposed changes to the NPPF.

A Regency palace of colour and sensation. Book review.

Delayed, derailed and devalued

How the UK’s planning crisis is undermining British manufacturing.

How much does it cost to build a house?

A brief run down of key considerations from a London based practice.

The need for a National construction careers campaign

Highlighted by CIOB to cut unemployment, reduce skills gap and deliver on housing and infrastructure ambitions.

AI-Driven automation; reducing time, enhancing compliance

Sustainability; not just compliance but rethinking design, material selection, and the supply chains to support them.

Climate Resilience and Adaptation In the Built Environment

New CIOB Technical Information Sheet by Colin Booth, Professor of Smart and Sustainable Infrastructure.

Turning Enquiries into Profitable Construction Projects

Founder of Develop Coaching and author of Building Your Future; Greg Wilkes shares his insights.

IHBC Signpost: Poetry from concrete

Scotland’s fascinating historic concrete and brutalist architecture with the Engine Shed.

Demonstrating that apprenticeships work for business, people and Scotland’s economy.

Scottish parents prioritise construction and apprenticeships

CIOB data released for Scottish Apprenticeship Week shows construction as top potential career path.

From a Green to a White Paper and the proposal of a General Safety Requirement for construction products.

Creativity, conservation and craft at Barley Studio. Book review.

The challenge as PFI agreements come to an end

How construction deals with inherited assets built under long-term contracts.

Skills plan for engineering and building services

Comprehensive industry report highlights persistent skills challenges across the sector.

Choosing the right design team for a D&B Contract

An architect explains the nature and needs of working within this common procurement route.

Statement from the Interim Chief Construction Advisor

Thouria Istephan; Architect and inquiry panel member outlines ongoing work, priorities and next steps.